“Geology of the Edwards Plateau and Rio Grande Plain Adjacent to Austin and San Antonio, Texas, with Reference to the Occurrence of Underground Waters” by Robert T. Hill and T. Wayland Vaughan published by the U.S. Geological Survey in 1898 (works volume 4, annual report volume 18, part 2, pages 199-321 with plates) captures the early years of artesian well wildcatting in the Austin to San Antonio to Del Rio area. The report also has some fabulous early photographs of key springs and flowing artesian wells in the area. Hill and Vaughan include quite a bit about the area’s geology (didja know that the Edwards used to be referred to as the Caprina limestone?), but I’ll focus on the hydrogeological bits here.

Of great interest to the authors, especially as they might relate to underground waters, were the springs along the edge of the plateau:

At intervals along- the interior boundary of the Rio Grande Plain from Austin to Devils River, through a distance of 300 miles, there is a series of remarkable springs which rise out of the ground. They do not break out from bluffs or fall in cascades, but appear as extensive pools, often in the level prairie. These pools or small lakes of limpid blue water find their outlet in swift and silently flowing streams.

The pools are carpeted with rare water plants, among which many fishes may be seen swimming. So transparent are these waters that objects 15 to 20 feet below the surface appear to be only a few feet away. They have been filtered by passing through the pores of the rocks for many miles.

The most conspicuous of these springs are near Del Rio, Brackett, San Antonio, New Braunfels, San Marcos, Manchaca, and Austin. In addition to these there are large springs north of the Colorado at Round Rock, Georgetown, Salado, Belton, and other places, as well as numerous small springs which need not be mentioned. The Cedar springs, north of Dallas, are probably the most northern of the line.

Hill and Vaughan discuss the half dozen artesian wells drilled in the Austin area, including wells sunk at the capitol, the Insane Asylum, St. Edwards, and the Austin Natatorium:

The Asylum well had a discharge of 150,000 gallons a day and threw the water to a height of 40 feet. The Asylum well is 1,975 feet deep. In the Asylum well the above-mentioned flow is separated by about 160 feet of limestone and shale from the third and lowest of the waterbearing beds, the basement, Travis Peak, or “Trinity” sands. These produce the purest water, and ordinarily the most, of all the waterbearing strata of the series. It will be seen that only one of the wells has positively penetrated the entire series of beds composing the Cretaceous system, thereby exploiting its fullest capacity and reaching into the underlying impervious Paleozoic formations. This is the well at the Insane Asylum.

The St. Edward’s well, sunk in the winter of 1892-93, is 2,053 feet deep

In St Edward’s well … the water comes within about5 feet of the surface and has to be pumped.

Two artesian wells have been bored by the State authorities on the capitol grounds. The first of these was in the year 1858 and was carried to a depth of only 471 feet.

Log of the Austin Natatorium artesian well, drilled by Hugh McGillivray, at the corner of San Jacinto and Fifth streets, Austin, Texas. The flow is about 250,000 gallons a day, and is increasing; temperature, 100°.

A valuable contribution to the extent of the artesian field in Travis County was made by the drilling of the well at Manor, in 1895. Quantity of water discharged per hour, 4,166 gallons. Size of discharge pipe, 6 inches. Temperature of water, 93°. Water will rise in pipe about 30 feet above the surface. The first effort to dig this well failed, as it caved in at the depth of about 1,100 feet. The present well, bored by Mr. J. Eppright, was finished about February 13, 1896, and cost $4,000.

“[We] have referred all the wells to a common geologic datum—the top of the Shoal Creek limestone…” The Shoal Creek limestone is now known as the Buda limestone.

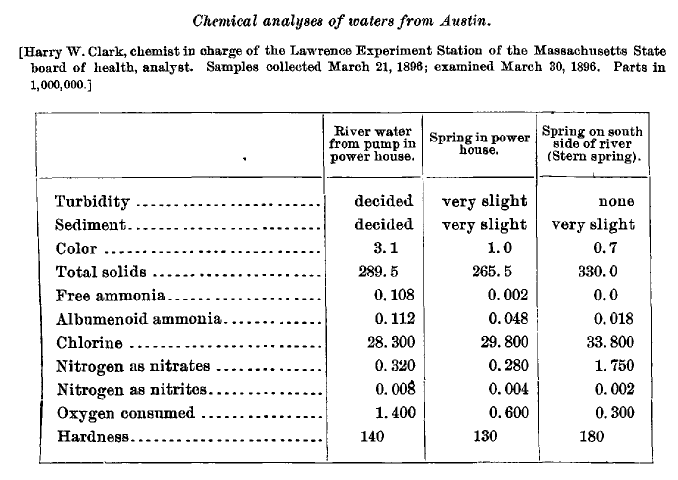

Many of the wells drilled in the Austin area at this time were not fresh. For example, the Natatorium well sunk at San Jacinto and Fifth had total dissolved solids north of 10,000 parts per million (see table immediately above).

Down in San Marcos there was, of course, San Marcos Springs, but also the recently drilled well for the fish hatchery, a well that made the national papers after producing blind critters from the depths (including Satan!).

At the village of San Marcos a great group of springs breaks out at the foot of a north-south line of bluffs making the Balcones scarp line in this region, and form the source of a beautiful river flowing 57,000,000 gallons per day. This has long been a famous resort in Texas on account of the exquisite aqueous flora and the beauty of the water. The springs form a lake nearly half a mile long, and its runoff forms the San Marcos River. At the lower end of the lake a mill and an ice factory are run by its water, and the United States Fish Commission has established a culture station here. While none of the water is utilized in irrigation, there is no reason why such a volume of water should not be used to irrigate considerable areas of the fertile Black Prairie lands.

Two records of an artesian well drilled for the United States Fish Commission at San Marcos in the year 1895 afford the most complete well section we have been able to obtain in the Rio Grande Plain. The well was drilled to a depth of 1,490 feet, and when stopped was still in the Cretaceous formations, about 175 feet above the estimated base of the Asylum well, at Austin.

There are one or two elements of perplexity concerning the San Marcos well which also present themselves at San Antonio. It is located almost upon the line of a great fault, which may be seen on the west side of the spring pool a short distance from the well. It is possible that the drill hole may cross this fault line not far below the surface, and that the so-called caverns are its waterworn fissures. The fact that this water was full of peculiar cave-inhabiting animals indicates that there are cavities beneath the ground, the extent of which, however, can not be stated. These maybe pockets, such as are seen in the outcrops of the Edwards limestone, or they maybe extensive caves, like the Hillcoat caverns of Edwards County. The fact that the drill passed through only 2 feet of cavity rather opposes the latter hypothesis.

For New Braunfels, Hill and Vaughan quoted Dr. Evermann:

There are a great many springs in the vicinity of New Braunfels, the principal group being known as the Coma] springs. There are several springs in this group situated upon the land of Mr. Joseph Landa, a little over a mile northwest of New Braunfels. The largest of these flows, perhaps, as much as 50,000 gallons per minute, and is certainly a magnificent spring. The other springs of the same group flow at least as much more.”

The main spring comes out near the foot of a limestone hill, and after running rapidly for a short distance over a pebbly bottom and in a narrow channel, it widens out into quite a pond with mud bottom and filled with vegetation. This pond also receives the water from numerous other springs, and has its outlet in Comal Creek (or the Rio Comal), which, after a course of2 or 3 miles, joins the Guadalupe River. The water of these springs is, of course, very clear. The temperature is 75°.

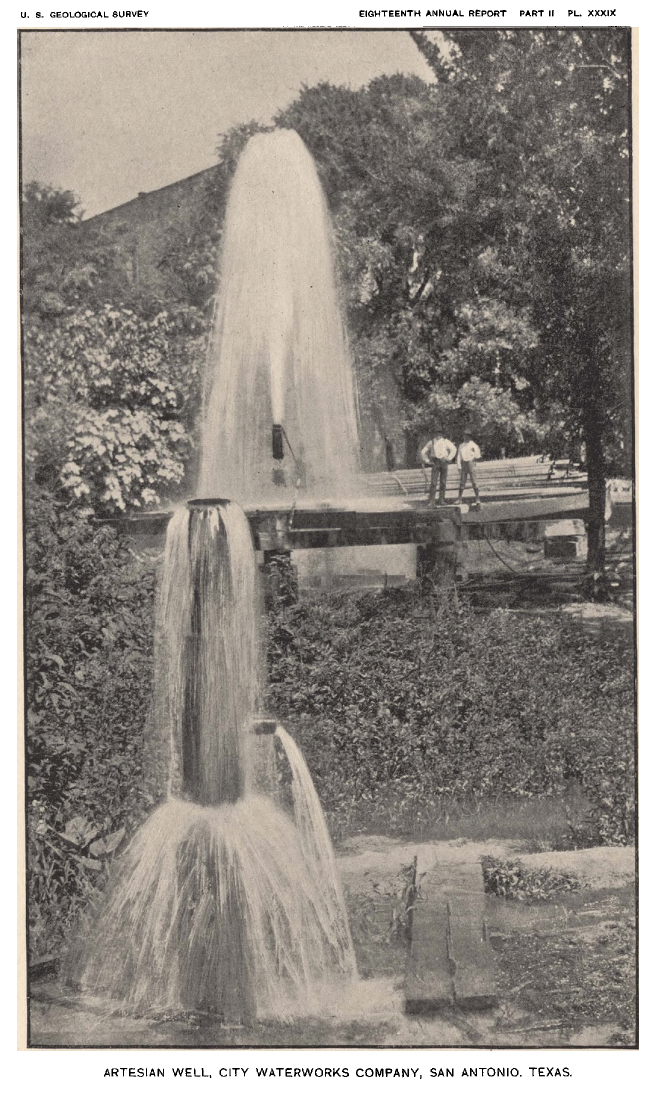

Hill and Vaughan identified 40 artesian wells in the San Antonio area and, interestingly, noted the gradual failure of San Pedro and San Antonio springs due to artesian well production. The wells included those drilled by Colonel C.M. Terrell, the Menger Hotel, the Santa Rosa Hospital, the city, and the Crystal Ice Company.

Many of the large springs, and some of the most noted of their class, occur in the vicinity of San Antonio, the largest being at the head of the San Antonio River, a few miles north of the city. Until recently these flowed out of the ground in great volume—27,000,000 gallons per day—forming an exquisite lake, the run-off of which is the San Antonio River, which flows through the heart of the city of San Antonio and supplies it with water.

Below this group of springs and upon the banks of its outflow was situated one of the most ancient Indian settlements, or pueblos, of Texas. The early Spanish priests, appreciating the beauties and natural advantages of the place, located several missions there within a short distance of one another. The natives were employed in the cultivation of farms and gardens irrigated by the spring waters. The ancient acequias or ditches, followed by the older streets, shape the present outline of the city.

The spring-fed river furnished, until recently, water for the city of 48,000 inhabitants without very appreciably diminishing its volume. Many acres of gardens and farms were irrigated, and there was sufficient water to irrigate many more. As elsewhere shown, the flow of the river has been recently seriously diminished by the drilling of numerous wells around San Antonio.

The San Pedro springs are about 2 miles southwest of those above mentioned, at the head of the river. Besides supplying an irrigation ditch they constitute the nucleus of handsome pleasure grounds. The springs here break out of fissures in the Gryphoea aucella beds of the Austin chalk. Their flow is estimated at 9 second-feet, or 6,000,000 gallons per day.

A large number of wells have been drilled in and around the city of San Antonio. They occur in nearly all parts of the city and its adjacent suburbs…

“[We] have referred all the wells to a common geologic datum—the top of the Shoal Creek limestone…” The Shoal Creek limestone is now known as the Buda limestone.

units in parts per million

thanks Robert! These guys were amazing scientists as you and others have long pointed out. As you note, it is interesting that in 1898 (and before) they understood the hydraulic connection of the artesian wells to springflow decline in the San Antonio area. I wonder why these guys were not testifying in the 1905? East case–if that would even make sense. Thoughts on that?

FYI Bluntzer’s detailed paper on the Capitol artesian wells is here: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56e481e827d4bdfdac7fbe0f/t/56f87ea14c2f85720ce5e7ad/1459125947263/Bluntzer%2C+2006%2C+History+of+water+wells+at+State+Capitol.pdf

LikeLike

As someone once explained to me, legal cases are about finding resolution, not truth. More broadly, my guess is that William East (due to funding limitations) or East’s attorney (due to legal strategy) didn’t employ a scientist to help out with the case. I think East and his attorney were fielding an uphill battle to begin with since Texas had adopted the English Rule as its foundational law.

Bluntzer’s paper is a classic! Maybe AGS needs a field trip on artesian wells sometime!

LikeLike

Help me understand. In Austin, they claim one well at the Capitol and one at the insane asylum, but they don’t explain why anyone would drill two wells at the same place. Must be a typo.

LikeLike

There were actually three wells drilled at the capitol by the time Hill and Vaughan published their report (see the link to Bluntzer’s paper in the previous comment). In the mid-1800s, deep driling was still somewhat experimental and trial by error, so it was not uncommon for wells to fail to reach their desired depth due to equipment failure or running out of funds. Plus, there was always some irritating hydrogeologist saying “if you had only gone deeper…”.

The first well was damaged when the previous capitol buliding burned down; the new capital building sits squarely on top of the well (and legend has it that it still leaks into the basement). The third well was drilled several feet away from the second after the drill string was lost in the second well somewhere in the Edwards. The third made it to the Trinity.

Thanks for the comment!

LikeLike

Thank you very much for the valuable information, Robert! It was interesting for me to see highly flowing wells in City of San Antonio at the end of 19th century when it’s population was only 53,000 people… 🙂

LikeLike