I’ve always loved art by the ancients, whether its petroglyphs (etchings in stone) or pictographs (paint on rock). I went to college amongst the rock art of New Mexico, and the drawings in the caves of Lescaux, France, made some 16,000 years ago, brought a tear to my eye when I visited them a couple decades back. When I moved to Texas and heard that there were pictographs along the Pecos River, I got down there as soon as I could to see the panel at Seminole Canyon. There’s something magical about people documenting their lives thousands of years ago and reading their thoughts today.

I don’t remember when I first heard about the 4,000-year-old White Shaman panel, but when I did, someone told me it held a map of the springs along the Balcones Escarpment. Soon after I started work at The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, I met Dr. Mario Garza and Maria Roche of The Indigenous Cultures Institute. Mario and Maria trace their heritage to the Coahuiltecans whose territory included northern Mexico and South Texas before Europeans disrupted the old way of life. The Coahuiltecan creation story holds that they were born from the underworld, emerging into the aboveworld through San Marcos Springs. In other words, Coahuiltecans were born of groundwater.

What’s that? Rock art? A groundwater connection? And a chance to eat the refried beans at Don Marcelino’s? Where do I sign up!?!?! As it turns out, it’s relatively easy to see the White Shaman since the Witte Museum offers tours almost every-Saturday during the off-summer months. The bride and I woke up early on a recent Saturday and high-tailed it to the meeting site a few miles west of Comstock (just west of Seminole Canyon). The hike down and back was moderate with some of it chained due to steepness, but the views of the Pecos River Valley, now partially underwater from Lake Amistad, were spectacular. After a short, final, steep ascent, the White Shaman panel unfurled before us.

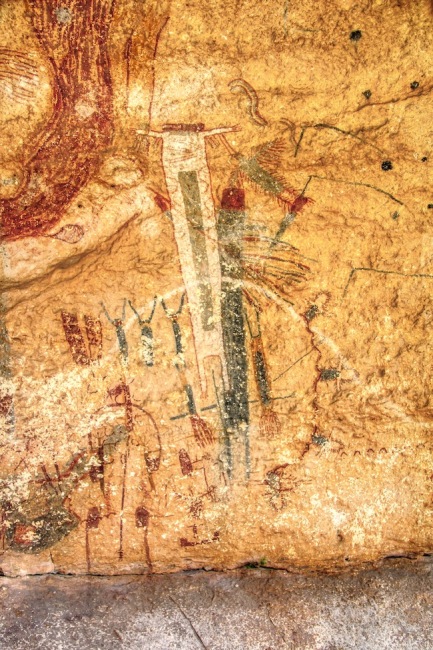

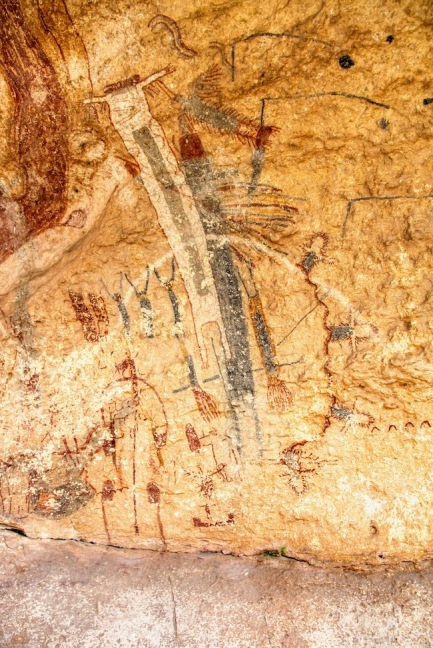

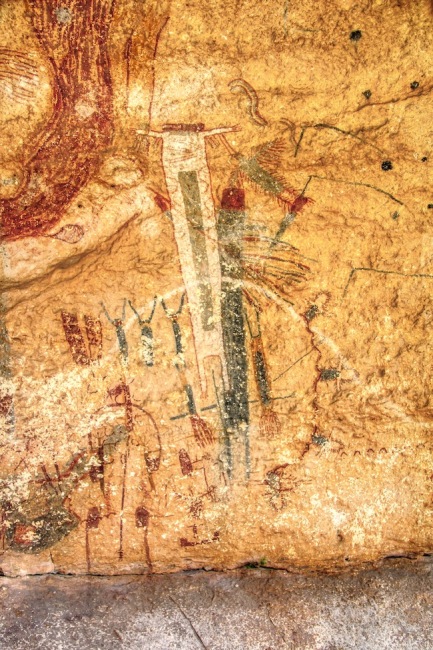

At first blush, the individual elements of the panel appear to be random and the work of numerous ancient passersby. This was the initial thought of archeologists as well. However, Carolyn Boyd, a muralist at the time she first saw the panel, recognized a coherent composition. And, indeed, once you look closely, you see it. There’s a rhythm to the composition as well as cross-canvas connectors. Inspired, Boyd went back to school to earn a Ph.D. in archaeology and dedicate herself to documenting and understanding the White Shaman panel and the hundreds of other panels not swamped by the lake.

Boyd and her collaborators used in-situ techniques to verify that the White Shaman Panel was, indeed, a piece painted at one time. Furthermore, the four colors in the painting were each done separately (first black, then red, then yellow, then white) suggesting that each element of the panel and how each element relates to other elements have meaning. As Boyd states, “Nothing in this panel is random or arbitrary; everything has its place and purpose.” In short, the panel is a coherent story.

In 2016, Boyd published a book, The White Shaman Mural, where she convincingly uses the creation stories of the Huichol and Nahua (Aztecs) to translate the major elements of the White Shaman Panel. Some amazing (to me) aspects of Boyd’s analysis were that (1) there is still a people (the Huichol) with a direct connection to their pre-European culture (in part because they are blessedly stubborn) and (2) there are still over a million people in Mexico who still speak the language of the Aztecs. Even more surprising is that both of these cultures have belief systems that carry back to the imagery on the rock cliffs of the Lower Pecos. In fact, the rock cliffs of the Lower Pecos are the oldest documented evidence of these religions (although Boyd is careful to note that this does not mean that the religions originated from this area).

The creation stories of the Huichol and the Nahua are mostly the same but with some variations, the details of which read like Mulholland Drive-era David Lynch with interweaving storylines that take place at the same time at the same place with entities in simultaneous multiple forms. The White Shaman Panel tells the story of the birth of the ancestors from the watery underworld. The five dark “shamen” are the primordial ancestors, each one carrying torches to ignite the sun. They also serve as cosmic pillars to hold up the sky.

The mostly white undulating line that cross-cuts the entire panel represents the sun’s elliptical path, aka the Flower Road, followed by a caterpillar toward the east, where the sun first rises. On the left side of the panel (left is east) is Dawn Mountain where the sun is born, and on the right side of the panel are the Dark Waters of the Underworld (so it was not only the Texas Supreme Court who thought groundwater was secret, occult and concealed…). There are also celestial deer that lead the primordial ancestors along the caterpillar’s path toward Dawn Mountain. I’ll end my most-likely flawed summary there since it seems that you need peyote to understand the full story:

“The deer guiding the primordial ancestors to Wirikuta was Tamatsi Parietsike (Elder Brother of Dawn). He is Master of the Hunt, shooter of arrows, and owner of the game. He is also Venus as the Morning Star. His arrows are rays of light with powerful transformative capabilities. Upon reaching Dawn Mountain, this celestial master of the hunt shoots the deer, who is at the same time himself. In his role as hunter, he is the Morning Star, and as prey, he is the Evening Star. His is both sacrificer and the sacrificed; predator and prey; hunter and hunted. Once slain, he transforms into his later ego, and as a result of this act of self-sacrifice, the heart (iyari) of the deer (Evening Star) is transformed into peyote, which is Morning Star and the sun.”

The book, of course, has much more detail, and I encourage you to get it. Be forewarned that it is a bit academic but still relatively understandable (as much as you can make the above understandable). It does inspire me to learn more about Huichol and Nahua beliefs and writings.

Garza believes that the pictograph to the lower right of the White Shaman is a map of the springs along the Balcones Escarpment showing the arc of the Escarpment and the location of Barton, San Marcos, Comal, and San Antonio/San Pedro springs.

It’s an intriguing interpretation. The springs are marked by black (which represent the underworld) dots lined with red “hair” and negative-space anthropomorphic appendages lined with red hair (fountains?). Red is used to denote flowing water and the aboveworld. “Hair” is used to prevent a soul from leaving a body. The white line crosses San Marcos Springs, which Garza interprets as the place where his Coahuiltecan ancestors were led to the surface by the celestial deer. The two San Antonio springs seem to be marked by two outflows on the panel.

Water is important to any society, and you have to believe that it was critically important to the ancient Coahuiltecans in this dry part of the world. Furthermore, the Coahuiltecan creation story involves, essentially, springs. So it’s perhaps not a stretch to think that springs would make an appearance on such a panel. The scientist in me wonders why the panel doesn’t show Las Moras and San Felipe springs, especially since these are the springs of the Lower Pecos area where the panel was painted. There are red dots that swing with rhythm to “the west” of the black dots approximating the swing of the Edwards Plateau to the west, and why would those springs be red with no hair?

Las Moras and San Felipe springs are more distant and disconnected from the escarpment than Barton, San Marcos, Comal, and San Pedro/San Antonio springs (although the Pedro/San Antonio springs are in transition in their location from the escarpment). Perhaps Barton, San Marcos, Comal, and San Pedro/San Antonio springs are special because they appear orographic (moutainous) at the transition from the coastal plains to the Hill Country and the others do not. These orographic springs are therefore like Dawn Mountain, and therefore holy, while the others are simply water supplies and therefore red (or not shown). Furthermore, since east and west are shown in the panel from the perspective of the anthropomorphs, the bend of the escarpment is wrong from their perspective.

Boyd says nothing in her book about the White Shaman Panel showing a map of springs, but she also leaves much of the panel’s details unanalyzed. And if the panel does show a map of the springs, it’s probably lost to (documented) history since that would be a regional story not likely included as part of the Huichol and Nahua narratives. I’m not going to argue with Dr. Garza with the springs interpretation: belief is belief (and it is believable). Studies have shown that oral traditions remain amazingly intact over thousands–even tens of thousands–of years.

And the White Shaman? Turns out she is (probably) the headless moon goddess whose light led the ancestors to Dawn Mountain. She is associated with rain and helping a single man survive a great flood (note that there is a person in what appears to be a canoe below her feet).

Rain, floods, occultish groundwater, and springs. The White Shaman Panel not only tells the creation story of Mesoamericans but also of water in Texas. Boyd compares the White Shaman Panel to the Sistine Chapel. It is, indeed, the Sistine Chapel of Texas.

Serendipitously, I was in Val Verde County to talk about the springs of the Lower Pecos area, including San Felipe Springs, and the protection of those springs. Instead of pigment and a rock wall, I painted my story with PowerPoint. Thousands of years separate us, but our stories remain the same…

Side notes on the Coahuiltecans: There is evidence of human activity in the Lower Pecos as far back as 11,000 years ago. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca was the first European to visit the South Texas area in 1534–1535. After disease probably wiped out 90 percent of the natives, the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 in New Mexico caused the Apaches to move into Coahuiltecan territory along the Balcones Escarpment, driving the Coahuiltecans toward the Gulf Coast. In turn, the Comanches drove the Apaches from the Balcones Escarpment in the mid-1700s toward the Gulf Coast where the Apaches took control of the rest of the Coahuiltecans’ range. As a result, Coahuiltecans made their way to the Spanish missions in the San Antonio area as unskilled labor where they were eventually absorbed into Hispanic culture by 1900.

Random (but delicious) side notes on the Huichol: The Huichol believe all water originates from the sea and is carried through the underworld by aquatic serpents (interestingly, the Bible’s theory of springs also holds that water originates from the sea). “In this [Huichol] universe, feminine forces of the rainy season and underworld are engaged in a constant battle with the light, masculine forces of the dry season and world above.” Procuring peyote is thought to prevent drought. For the Huichol, S-shapes refer to rain serpents. Salamanders prod the clouds into letting go of the rain. Turtles are emissaries of the Rain Goddess that purify water and replenish underground springs. Gods are supposed to reside in swamps, waterholes, and springs.

Some references:

https://archive.org/details/symbolismofhuich00lumh/mode/2up

https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/bmcah

https://www.nbclearn.com/portal/site/learn/cuecard/70204

A Nahua symbol for water

Holes for grinding pigment (and storage?)

Thank you for this!

Christy Muse 512.560.3135

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Why isn’t the San Felipe Springs thought of being part of the mural? It’s the closest. Or is it part of a larger body of water depicted? Our springs is beautiful and after living in Austin, I think prettier than Barton and San Marcos. But this underdog reputation has done nothing for its protection and preservation.

LikeLike

It’s all subject to interpretation (but I do show San Felipe Springs on my interpretation of the map). There might even be a representation of Goodenough Springs further to the west and perhaps Leona Springs between Las Moras and San Antonio/San Pedro. As to why what might possibly be San Felipe Springs is not represented with the color of the underworld, I’m not sure. Perhaps it’s because those springs (that is, those without black) are close to the Rio Grande and thus not as critical as stand-alone water sources? Maybe they were not as reliable as the other springs during severe drought and therefore not considered life-giving (see Las Moras Springs these days)?

LikeLike